Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel made a bunch of promises three years ago when he was running for office—especially when it came to education.

He’s checked off some of them – a longer school day, more preschool, a focus on principals.

But now his administration is ramping up attention to one the stickiest challenges: re-enrolling the city’s more than 50,000 dropouts.

Grassroots efforts

For years–long before Emanuel pushed for a systematic way of enrolling dropouts–Pa Joof has been taking a shoe-leather approach to getting students back in school.

Joof is the head of Winnie Mandela, an alternative high school on 78th and Jeffrey in the city’s South Shore neighborhood. Mandela is one of four schools run by Prologue Inc., a non-profit founded in 1973 to help disadvantaged neighborhoods. Prologue started running alternative schools for Chicago Public Schools in 1995.

On the first day of school, WBEZ visited Winnie Mandela High School to watch Joof and his team at work.

“This is the little van that we use for basketball games,” Joof tells me over the rumble of the van’s engine starting up. It’s almost lunchtime and he’s about to hit the streets with two of the school’s security guards–Dominick Muldrow and Dessie McGee–who double as recruiters and mentors.

“We get the flyers and we put them up there,” Joof explains. “We know the corners that [kids are on], the areas that they go to.”

“Like the ones walking there,” McGee says, pointing out the van’s backseat window.

“What’s happening? Today is the first day of school man, what’s happening?” Joof shouts out the window.

“Ya’ll registered for school?” Muldrow asks.

“He’s 24!” says one of the two men on the sidewalk.

“Ah, he don’t look that old,” Muldrow says

“Maybe you all know someone that’s trying to get back in?” McGee says, leaning to the front seat window to hand the men flyers about the school. “Share these flyers with them.”

“This a high school?” one of the men asks.

“Yeah, right on 78th and Jeffrey,” McGee replies.

“My little brother, we’re trying to get him back in there,” the man says. “He got like six credits, no, three. We’re trying to get him back in. What ages?”

“Seventeen to twenty-one!” McGee says.

That’s the age range when kids can still re-enroll in high school, according to CPS. When Emanuel took office in 2011, CPS ran the numbers to find out exactly how many students had dropped off the attendance rolls before graduating, but were between 13 and 21. The number was close to 60,000.

During his first 100 days in office, Emanuel’s directive was clear: find those kids and get them back to class.

A systematic approach

Molly Burke is leading the district’s Student Outreach and Re-Engagement program, or SOAR.

“This is the first program we have where we’ve gotten a list of all the dropouts and proactively gone after them,” Burke says, echoing what her predecessor told WBEZ in 2011.

The effort pulls data from the district’s student records system to identify kids who have left school before graduating in the last few years.

“Throughout the summer, they had a list that were all the students that dropped last year and the year before,” Burke explains. “So we went after those students who weren’t active at the end of last school year. And now that school starts, they start to get the list of the kids that have dropped or who did not arrive.”

District officials formally announced the SOAR program last year and with it, three official re-enrollment centers were opened. Sean Smith oversees the SOAR centers, located in Little Village, Roseland and Garfield Park.

So far, 1,700 students have come through the SOAR centers and 130 have already gotten their high school diplomas. Smith says they want to enroll an additional 3,000 this year.

“That’s a large goal for our team,” he admits, noting that each staff member would be bringing in 15 new students every week. At each center, there are five re-engagement specialists that basically do what Prologue has been doing, only with names, addresses and phone numbers from downtown.

After a student decides to re-enroll, they go through a two-week program at a SOAR center that helps them set goals and choose a school.

Getting the diploma

Most of the students re-enrolling won’t go back to a traditional high school. For one, many dropouts would age out of eligibility before they could feasibly earn enough credits to graduate. And Smith says putting teens back in an environment that already didn’t work for them, usually doesn’t make sense.

But students may not be going to one of the city’s longstanding alternative schools, like Winnie Mandela, either.

That’s because CPS recently expanded the number of alternative programs available to students, including many online schools and several run by for-profit companies.

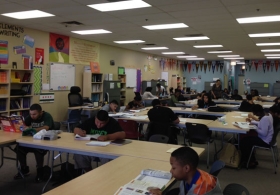

One of those, Pathways in Education, is located in a strip mall at 87th and Kedzie. The school spans two spaces in this sprawling commercial building. One is a wide-open space, the size of a retail store, where about a dozen teachers sit at desks lining the outside walls and teens study at tables in the middle of the room.

Student James Cicconi goes here, but used to go to Kennedy High School on the Southwest Side. He says he skipped a lot during his freshman and sophomore years.

“When you ditch school, it’s like an addiction,” Cicconi says. “It’s like right away you do it once and you’re want to do it again and again and before you know it you’re gone twenty days out of the month.”

When he started his junior year, Cicconi says the staff at Kennedy told him, “Even if you do all of your stuff, there’s not enough time for you to graduate. So you can either wait for us to kick you out or you can do this program.”

CPS requires 24 credits to graduate. When Cicconi left Kennedy, he only had four.

“Because of the credits and how slow it is with getting them, and how much you have to do just to get a half credit for one class, they told me, even if I did night school, summer school, there just wasn’t enough time for me to graduate on time,” Cicconi says.

He started classes at Pathways last winter and comes roughly three hours every day. So far, he’s earned twice as many credits as he did in two years at Kennedy.

CPS officials say the non-traditional setting and online classes help kids work at their own pace. But, nationally, investigations of online schools have found the courses often aren’t as rigorous and can cheapen the value of a high school diploma.

Cicconi says classes are easy, but that he’s able to focus better without lots of other kids around, goofing off in class. He says schools like Pathways are good for students who might have what he calls “an authority problem”

“People come up with their own agenda and their own rules and I feel that, when you come up with your own rules, you have more of an obligation to do it because you’re leading yourself,” Cicconi says.

Back in South Shore, where Pa Joof and his team are doing outreach without a list from CPS, Dominick Muldrow turns the corner onto Jeffrey Boulevard, to head back towards Winnie Mandela High School. Muldrow and McGee, the other recruiter, both dropped out and earned their diplomas through alternative programs.

“I relate to a lot of the guys, you know,” Muldrow says. “But at the end of the day, what it all boils down is, you’re gonna need a high school diploma.”

That is the message the district hopes to get to a least 3,000 more kids this year.